Tuesday, June 19, 2012

Lemberger: love it, hate it

I wouldn't dare try to add any notes.

Sunday, February 26, 2012

Meine Schülerin

In Vom ersten Zug an auf Matt Diemer refers to “meine Schülerin, Frau Oesterle.” The noun would normally translate as the feminine form of student, or pupil, but in Diemer’s case I would imagine that he intended it more in the sense of “my disciple.” Still, he was not too proud to include this miniature in his book:

Decades later, not long before her death, Elisabeth Oesterle spoke of Diemer as he was in those days:

Her husband operated a little cheese dairy in Biesenberg. Diemer often visited her. He was very poor and she gave him to eat and to drink. Once she presented him with a coat (I believe a winter coat). Some days later she heard that he had sold it--probably to finance his worldwide correspondence. She was deeply saddened by this.

Related post: You don't bring me flowers...

Tuesday, September 27, 2011

Problem number one

From this week’s TWIC comes the latest example. White tries Edgar Sneiders’ optimistic 4.Qh5 and ends up struggling for a draw. The game follows a defensive line often played by Klaus Nickl, and I’ve inserted several of his games in the notation. Other than that you’re on your own.

Monday, August 8, 2011

A mixed bag

Mondays are fun days here. I look forward to the crop of games from The Week in Chess. Today’s issue brought forth more BDGs and close relatives than usual, but a mixed bag of wins, losses, and draws (how chess-like). I didn’t find anything especially of interest: no theoretical innovations, no spectacular combinations, not even an entertaining blunder of note. See if you agree.

Monday, October 4, 2010

One Little Lemberger at the Olympiad

Tuesday, July 7, 2009

Think Like a Grandmother

My friend, Peter Atzerpay, the well-known private detective and strong amateur chessplayer, called last month immediately upon receiving his copy of BDG World 45.

"Purser," he said, "you're starting to think like a grandmother!"

Having once had two adorable grandmothers, I was inclined to take this as a compliment. But before I could thank him, he continued, "Now look at game 964," he said. "At the end you give all those fancy lines under variation a, 22...Ke6. Reminds me of my grandmother serving tea, all those little lace dollies and things. Why not just 23.Qxg6+ Kxe5 24.Re4#?".

What could I say? "You're right, Pete."

"And variation b, after 22...Kf8, etc, etc, makes no sense either. What you probably meant was 27.Rg4+ and mate in two.”

"Right again, Pete." I could only hope my contriteness projected over the phone lines despite the AT&T breakup.

"Well, you can do better," he said. "Get rid of that little old lady thinking of yours, all that lace and cobwebs analysis. Flush out your mind, man."

And with that he was gone, off on some important new case, I imagine. But his words stung. Nothing hurts like the truth (except maybe a back-rank mate), and when I started looking through some of my games I had to admit he was right. Let me show you what I mean:

Purser,Tom (USA) - Gaberc,J (Yugoslavia)

Correspondence ICCF, 1979/80

Lemberger Countergambit

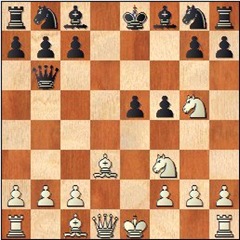

1.d4 d5 2.e4 dxe4 3.Nc3 e5 4.Nxe4 Qxd4 5.Bd3 f5 6.Nf3 Qb6 7.Neg5

7...e4 [7...h6 and now what??] 8.Bc4 exf3 9.Bf7+ Ke7 10.0-0

10...h6 [Up to this point we've been following Diemer-Schoenfuss, Rastatt 1954, which went 10...Nc6 11.Re1+ Kf6 12.Bxg8 Rxg8 13.Qd5 Nd8 14.Qxd8+ Kg6 15.Qe8+ Kh6 16.Ne6+ 1-0]

11.Re1+ [11.Bxg8 also works]

11...Kf6 12.Qd8+ Ne7 13.Bb3!

13...hxg5 White's 13th looks simple now, but I worked hard on my analysis of Black's possibilities: [See the link at the end of this game.]

14.Qe8 Nd5 [14...Qxb3 15.axb3 Nbc6 probably allows Black to put up the strongest resistance.]

15.Bxd5

15…Qxf2+ 16.Kxf2 Bc5+ 17.Kxf3 Rxe8 18.Rxe8

18...Nd7? [18...c6? 19.Rxc8 cxd5? 20.Rxc5] 19.Re6+ Kf7 20.Bxg5 Kf8 [20...Nf8 21.Rc6+ Ne6 22.Rxc5] 21.Rae1

21...Nf6? 22.R6e5? [The grandmother moment--missing the simple mate in two with 22.Rxf6+ gxf6 23.Bh6# In my defense, I was playing over 100 games at the time and had already marked this one up in the win column, so didn't give it any time (a typical grandmotherish excuse).]

22...Nxd5 23.Rxd5 Bd6 24.Bf4 b6 25.Bxd6+ cxd6 26.Kf4 Bb7 27.Rxf5+ 1-0.

To be continued…

Play through this game with additional notes and download PGN here.

Monday, June 29, 2009

Keres, Diemer, and the BDG

Keres,Paul – Luhmann

Correspondence , 1933

Lemberger Countergambit

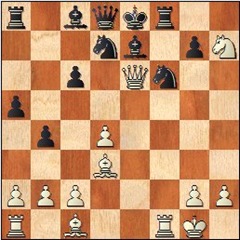

1.e4 e5 2.d4 d5 3.Nc3 dxe4 A Lemberger by other means. 4.Nxe4 Nd7 5.Nf3 Ngf6 6.Nxf6+ Nxf6

7.Nxe5 [A couple of grandmasters continued here with 7.Bd3 c5 8.dxc5 Bxc5 9.0-0 h6 10.Qe2 0-0 11.Bf4 Bd6 12.Nxe5 Qc7 13.Rad1 b6 14.Bg3 Rd8 15.c3 Bb7 16.Bb1 Ba6 17.Qxa6 Bxe5 18.Bxe5 Qxe5 19.h3 Qc7 1/2-1/2 Tiviakov,S (2608)-Hodgson,J (2640)/Istanbul 2000] 7...c6 8.Bd3 Qc7 9.Bg5 Be7 10.0-0 0-0 11.Re1 b6

12.Re3 [12.Qf3 Bd7 (12...Bb7? 13.Bxf6 Bxf6 14.Qf5) 13.Be4+-] 12...h6?? Usually a mistake, as it is here. [12...Nd5 13.Bxe7 Nxe3 14.Bxh7+ Kxh7 15.Qh5+ Kg8 16.Bxf8 Nf5+-] 13.Bxh6!+- gxh6 [13...Re8 14.Rg3 Bf8 15.Qf3+-] 14.Qf3

14...Ne8? [14...Nd5 is better. 15.Qg3+ Bg5+/=] 15.Qh5+- Bg5 16.Rg3 f6

17.Ng4 [17.Rxg5+! fxg5 18.Bc4+ wins easily.] 17...Ng7?? [Black was still in the game with 17...Bxg4 18.Rxg4 f5] 18.Nxh6++- Bxh6 19.Qxh6 f5

20.Re1 [I've read that Keres played as many as 150 correspondence games at once during this time, which may account for his overlooking 20.Bc4+ Be6 21.Bxe6+ Rf7 22.Qxg7#] 20...Qf7 [20...Ba6 21.Bxa6 b5 22.Qe6+ Rf7+-] 21.Ree3 1-0

[21.Ree3 b5 22.Rg6+-; but 21.Bc4 still mates quickly: 21...Be6 22.Bxe6 Qxe6 23.Qxg7#]

In his book, Vom Ersten Zug an auf Matt!, Diemer included this fragment of a game with Keres as game 167:

Diemer,EJ - Keres,Paul

Correspondence, 1935

Blackmar-Diemer Avoided

1.d4 d5 2.e4 dxe4 3.Nc3 g6

4.Nxe4 Bg7 5.Nf3 Nf6 6.Bd3 Nbd7 7.Neg5 0-0 8.h4 h6 9.Ne4 Nxe4 10.Bxe4 Nf6 11.Bd3 Bf5 12.Bxf5 gxf5 13.Qd3 Qd5 14.Be3 Qe4 15.Qe2 Nd5 16.c3 a5 17.Nd2 broken off.

Play through the games and download PGN here.

Friday, June 26, 2009

Australian Lemberger

Stevens,Tristan (2006) - Xie,IM George Wendi (2402)

Oceania Zonal Gold Coast AUS (1), 20.06.2009

Lemberger Countergambit

1.e4 d5 2.d4 dxe4 3.Nc3 e5

The Lemberger Countergambit, not what a Blackmar-Diemer player wants. On the other hand, many BDG players enjoy playing the black side of it--I always did.

4.dxe5 Qxd1+ 5.Kxd1 Nc6 6.Nxe4 Nxe5 7.Bf4 Nf6

8.Nxf6+ [‹8.Bxe5 Nxe4 9.Bd4 Bg4+ 10.Be2 Rd8 11.Bxg4 Rxd4+-+] 8...gxf6 9.Nf3 Ng4 10.Bg3 Bf5 11.Bb5+ c6 12.Re1+ Kd7 13.Nd4 Bg6 14.Be2 h5 15.h3 Nh6 16.Bc4 Bc5 17.Nb3 Bb6 18.Bh4 Rhe8 19.c3 Nf5 20.Bxf6 Bxf2 21.Rxe8

21...Rxe8 [‹21...Kxe8 22.Ke2 Bb6 23.Kf3+/=] 22.Kd2 Be3+ 23.Kd1 Bf4 24.Bd4 h4

25.Bd3 [25.Bxa7? Be3 26.Nd4 Ng3-+] 25...Kc7 26.Kc2 Ng3 27.Bxg6 fxg6 28.Bf6 Re2+ 29.Kd3 g5 30.Nd4 Re3+ 31.Kc4 c5 32.Nb5+ Kc6 33.Nxa7+ Kb6 34.Nc8+ Ka6 35.Rd1 Re6 36.Be7 Nf5 37.Bxc5 b5+ 38.Kb3 Kb7

39.Ne7! Nd6 [39...Rxe7 40.Bxe7; 39...Nxe7 40.Rd7+] 40.Nd5 Nc4 41.Nxf4 gxf4

42.Rd7+??

[Too bad. White had good winning chances with 42.a4!

a) 42...Re2 43.axb5 Nd2+ 44.Kb4 Rxg2 (44...Kc8 45.Rg1) 45.Re1 Rg7 (45...Rg3 46.Re7+) 46.Re2;

b) 42...Re5 43.Bd4 Na5+ (43...Rg5 44.axb5 Ne3 45.Bxe3 fxe3 46.c4+-) 44.Ka3 Nc4+ 45.Kb4 Re2 46.axb5+-;

c) 42…Ne3 43.Rd2 bxa4+ 44.Kxa4 Kc6 (44...Nc4 45.Rf2+-) 45.Bd4+-]42...Kc6-/+ 43.Re7 Rg6 44.Kb4 Nxb2 45.Bd4 Nd3+ 46.Kb3 Rxg2

47.Rh7?? Now Black has mate in four. 47...Nc1+ 48.Kb4 Rb2+ [48...Rb2+ 49.Ka5 Rxa2+ 50.Kb4 Ra4#] 0-1

Play through the game and download PGN here.

Sunday, May 31, 2009

Black Blunders in the Blackmar

Over the years Niels Jørgen Jensen, of Copenhagen, contributed many articles and games to BDG World. Here is his first article we published, from the January/February issue of our third year, 1985.

We all know that if we let our opponent face a BDG we are more likely to finish him off quickly and brutally than if we play another opening, say the Queen's Gambit. Why is that so? What is it in the BDG that literally provokes our opponent to commit blunders? Well, to a certain extent it can be explained.

If we accept the fact that blunders do not appear totally haphazardly, it becomes clear that the answer must be closely connected to psychology. Chess is a mental struggle, and so chess blunders must be looked upon as psychological phenomena. Let us take a look at various categories of black faults and try to explain them. First, a game as study material:

Niels Jørgen Jensen - Steen Lynesskjold

Team Match, 1984

BDG (from Caro-Kann)

1.d4 d5 2.e4 Here my opponent sighed, "Blackmar-Diemer," thought for about five minutes, shook his head determinedly and played: 2...c6 3.Nc3 dxe4 4.Bc4 Nf6 5.f3 And now he realized that he had been fooled. Ten minutes thought. 5...exf3 6.Nxf3

6...e6 [Some people just don't play the obvious: 6...Bf5 ] 7.0-0 b5 8.Bd3 Nbd7 9.Qe1

Preparing for Qg3 or Qh4. I wouldn't develop my Bc1 until Black had had his chance to misplace his Bf8. 9...Be7 10.Ng5 b4 11.Nce4 a5 12.Nxf7 Kxf7 13.Ng5+ Ke8 14.Qxe6 Rf8 15.Nxh7 1-0

As you will admit, Black defended poorly. However, he is no weak player, and his weak moves do not occur incidentally but--as we shall see--can be psychologically explained.

In his excellent book, Psychology in Chess, the Russian GM Krogius distinguishes between three different types of blunders, which are all present in the above game:

1. The forward image occurs when the player transfers positions reached in his calculations or moves which have not yet been played to the actual position on the board. As Krogius expresses it: “The future possibilities become an obsession and are treated as real factors in the assessment of the current position.” Thus the player in whom a forward image has arisen tends to exaggerate threats. In the game above, the move 6…e6? is the result of such a forward image. Black knows that the BDG is a very sharp opening, he may fear a Bxf7+, and in his imagination he already sees an overwhelming attack with Ng5+ and Qf3--moves which in his mind are accepted as real. Perhaps he also sees the "ghosts" 6…Bg4? 7.Ne5 or 6…Bf5 7.0-0 followed by Ng5/Nxf7/Rxf5. At any rate, he decides on the "safe" 6…e6?, preventing the impossible sacrifice on f7. If you search your BDG literature (Freidl II, e.g.), you will find several similar moves, indicating that we are dealing with a common psychological pattern.

2. The retained image is the opposite of the forward image. Whereas the forward image leads to exaggerations of future possibilities, the retained image tends to narrow down the perception of the chess player, who plans his moves from a starting point which has become static, thus repressing the dynamic aspects of the position.

I think Krogius's retained image should be divided into two distinct subcategories:

a) Positions or possibilities previous in the game still influence the player's perception of the actual position on the board. After my game with Lynesskjold, he told me that he had not seen the possibility of 12.Nxf7 at all, a statement which at first seems amazing--after all Nxf7 is probably the most evident move in the entire game, so how could he miss it? The answer is really simple: once he had seen the possibility of a sacrifice on f7 (namely Bxf7), he had prevented it by 6 … e6. Furthermore, with 7 … b5 he had driven away the Bishop from the diagonal, so from moves 7 -12 in his mind a sacrifice on f7 was impossible. The board had changed, but the idea that a sacrifice had been prevented remained. As Krogius expresses it: “In this way the past continues its activity into the present to the extent of edging out reality.”

b) Elements in the position on the board become static and are transferred in an unaltered form to future lines reached in calculation. An example of this kind of retained image is found in the following game:Jan Sandahl – Emborg

Denmark, 1984

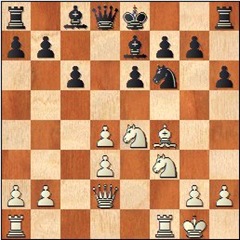

Lemberger Counter Gambit

1.d4 d5 2.e4 dxe4 3.Nc3 e5 4.Nxe4 Qxd4 5.Bd3 Nc6 6.Nf3 Qb6 7.0-0 Bg4 8.h3 Bxf3 9.Qxf3 Nd4 10.Qh5 Bd6 11.Be3

11...Qc6? 12.Bxd4 exd4 13.Bb5 1-0

The blunder 11 … Qc6? can only be explained by the second type of the retained image: the e5-pawn firmly separates the Qh5 from the crucial square b5 and blocks Black's imagination of the possibilities after a possible removal of the pawn.

3. Krogius's third category of faults arises from the recalled inert image. This image may arise when a player, trying to carry out a plan, fails to realize that the position on the board might have changed in a way which was not foreseen. The player fails to notice the dynamic powers of the position. Again as a first example my game above; after having played 6 … e6, Black must find another way to develop his Bc8, and as he finds 0-0 too dangerous before the Bd3 has been exchanged, he plans to play b4/a5/Ba6, but as he finally reaches the point where he is ready to play Ba6, the position has changed and is already lost for him.

As Krogius points out, the inert image often arises when a player is satisfied with his position and thinks that the game is already won for him. Probably this is the reason why the inert image is a very common cause for Black blunders against the BDG: one pawn up, Black often mechanically tries to exchange pieces, underestimating the dynamic power of the White position. Another example:

Erich Müller - N. J. Jensen

Correspondence, 1984/85

BDG, Euwe Defense

1.d4 d5 2.e4 dxe4 3.Nc3 Nf6 4.f3 exf3 5.Nxf3 e6 6.Bg5 Be7 7.Bd3 Nc6 8.Qd2 h6 9.Bf4 Nb4

If this is not correct, then the frequently played 8.a3 is a waste of time. Now the first exchange costs Black a tempo. 10.0-0 Nxd3 11.cxd3 c6 12.Ne4

and now Black felt that he only had to exchange a few more pieces before winning the ending with his extra pawn, his better pawn structure, and his pair of Bishops, so he played 12...Nd5? which of course is met by 13.Ne5 Now, 13 ... Nxf4 14.Qxf4 would be suicide, and the only move preventing an immediate disaster is the sad retreat 13...Nf6 but after 14.Qf2 White has a tremendous position.

Now we have examined some types of blunders, but we still have to explain why these blunders should be provoked by the BDG more than by most other openings. The answer to that, I think, is closely connected to the question: what makes some players better than others? One answer could be (Hartston / Wasen: The Psychology of Chess, p.55): "The skill of a master is assumed to be basically one of 'pattern recognition'" (rather than a skill of calculating many moves ahead/njj). The consequences of this are met in the highly recommended book, Chess for Tigers, by Simon Webb, where the author advises (p. 40) how one should play against "Heffalurnps" (very strong players): "Randomize! … so if you see a line which is difficult to judge, give it a try." (i.e., positions. where your opponent. cannot see any "normal" patterns/njj). "The sorts of positions which are particularly difficult to judge are those with a material imbalance, such as queen for two rooks, two minor pieces for a rook, the exchange for a pawn or two." In this category would also belong positions with initiative for a pawn, a strong attack for a piece, etc.--in short, the BDG!

One more thing pulls in this same direction: as pointed out by Tarrasch, who was a doctor as well as a chess master, an unforeseen sacrifice tends to arouse a state of shock in the opponent, disturbing his ability for calm and correct calculation. This state of shock, which might arise even when the gambit pawn is offered, then increases the possibility of the fault-provoking images dealt with above, since the ability of the player to overcome the gap between the position on the board and the one reached in calculation is reduced radically when he cannot recognize his usual patterns. Accordingly, the White chances will increase, simply because sacrifices on f7, Canal mates, etc., are standard patterns of every BDG player.

So--should the BDG not be "correct" (and I believe it is!), I think that any lack of "correctness" is more than offset by the psychological advantages it gives its supporters. I am sure you agree with the German player who called the BDG “Panneverdächtig” --blunder provoking.

Play through and download PGN games here.

Monday, December 22, 2008

Saturday, September 27, 2008

The Beginning of His Best Year (Part 1)

Saturday, August 9, 2008

The Sneiders Attack

4...exd4 5.Bc4 Qe7 6.Bg5 Nf6 7.Bxf6 Qxf6 8.Nd5 Qd6 9.0-0-0 Nc6 10.Ne2 g6 11.Qh4 Be6 12.Nf6+ Kd8 13.Bxe6 Qxe6 14.Nxd4 Nxd4 15.Rxd4+ Kc8 16.Rxe4 Bh6+ 17.Kb1 Qc6 18.Qh3+ Kb8 19.Nd7+ Kc8 20.Ne5+ Qe6 21.Nxf7 Qxh3 22.gxh3 Kd7 23.Rd1+ Kc6 24.Re6+ Kc5 25.Nxh6 and White won.

"Certainly a totally original game,” remarked E. J. Diemer in his chess column, which was reprinted in the second issue of Kampars’ Blackmar Diemer Gambit (March 1962). In fact this game was the stammpartie, the original example of what has come to be known as the Sneiders Attack in the Lemberger Countergambit. One may be at first tempted to dismiss White's early Queen excursion as a patzer's move, but Sneiders was a master, not a patzer. Closer examination reveals the move is not that easy to refute. In the November 1988 issue of BDG World I included a comprehensive overview of this variation, which is much too long to reprint here.In a 1987 letter to Anders Tejler, Edgar commented on his namesake.

Do you want to know the history of the Sneiders Attack and how it was born? Well, here it is: About 20 years ago when I was very active in the BDG movement I played in one OTB tournament 4.Qh5, which evidently was "the First", as Herr Diemer promptly honored me by attaching my name to this move.

Afterwards I had hardly any opportunity to play 4.Qh5, as in those days 3…e5 was very seldom played. So I never analyzed it and forgot the whole thing. Then I became dormant for about 10 years and did not play chess at all. I resumed my BDG games again after Walter Schneider coerced me to join one of his BDG tournaments. To my amazement I discovered that in the meantime lots had been written and analyzed about 4.Qh5. There were strong suggestions that 4…Nc6 refutes the Sneiders Attack. I do not know! I must say that in comparison to German BDG-ers I was the least knowledgeable guy on my own attack.

4...exd4 5.Bc4 Qe7 6.Bg5 Nf6 7.Bxf6 Qxf6 8.Nd5 Qd6 9.0-0-0 Nc6 10.Ne2 g6 11.Qh4 Be6 12.Nf6+ Kd8 13.Bxe6 Qxe6 14.Nxd4 Nxd4 15.Rxd4+ Kc8 16.Rxe4 Bh6+ 17.Kb1 Qc6 18.Qh3+ Kb8 19.Nd7+ Kc8 20.Ne5+ Qe6 21.Nxf7 Qxh3 22.gxh3 Kd7 23.Rd1+ Kc6 24.Re6+ Kc5 25.Nxh6 and White won.

"Certainly a totally original game,” remarked E. J. Diemer in his chess column, which was reprinted in the second issue of Kampars’ Blackmar Diemer Gambit (March 1962). In fact this game was the stammpartie, the original example of what has come to be known as the Sneiders Attack in the Lemberger Countergambit. One may be at first tempted to dismiss White's early Queen excursion as a patzer's move, but Sneiders was a master, not a patzer. Closer examination reveals the move is not that easy to refute. In the November 1988 issue of BDG World I included a comprehensive overview of this variation, which is much too long to reprint here.In a 1987 letter to Anders Tejler, Edgar commented on his namesake.

Do you want to know the history of the Sneiders Attack and how it was born? Well, here it is: About 20 years ago when I was very active in the BDG movement I played in one OTB tournament 4.Qh5, which evidently was "the First", as Herr Diemer promptly honored me by attaching my name to this move.

Afterwards I had hardly any opportunity to play 4.Qh5, as in those days 3…e5 was very seldom played. So I never analyzed it and forgot the whole thing. Then I became dormant for about 10 years and did not play chess at all. I resumed my BDG games again after Walter Schneider coerced me to join one of his BDG tournaments. To my amazement I discovered that in the meantime lots had been written and analyzed about 4.Qh5. There were strong suggestions that 4…Nc6 refutes the Sneiders Attack. I do not know! I must say that in comparison to German BDG-ers I was the least knowledgeable guy on my own attack.